I still sometimes think about the first season of HBO’s Westworld, which I devoured over a weekend back in 2016. The show's real revelation for me was how it brought to life one of psychology's most audacious theories: Julian Jaynes' concept of the bicameral mind.

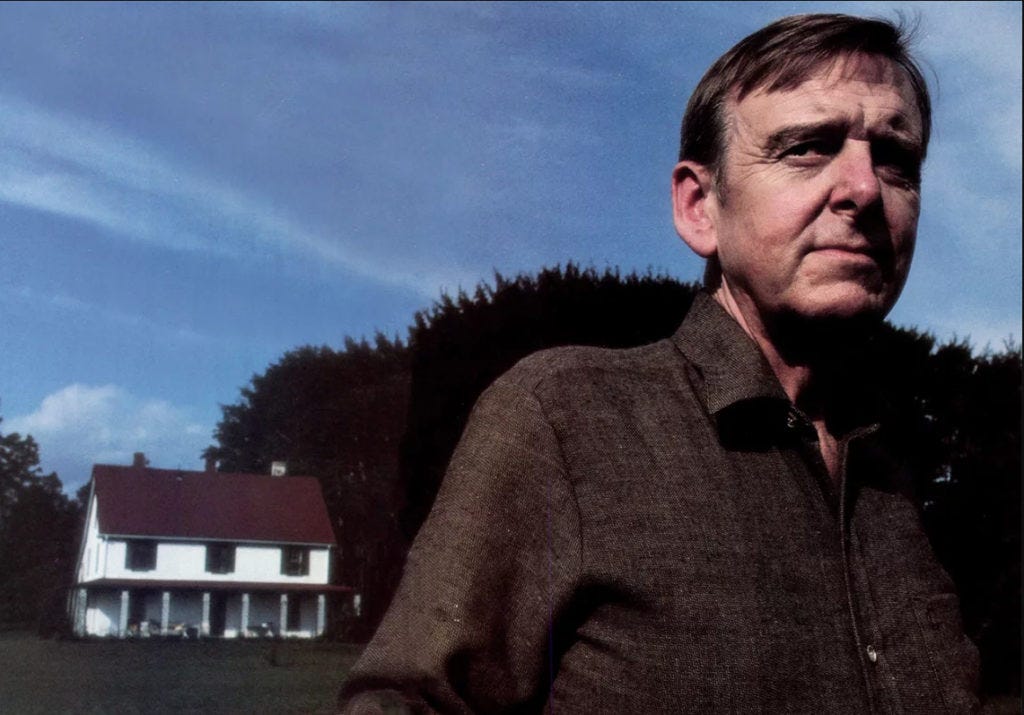

Julian Jaynes, a Princeton psychologist, published The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind in 1976, proposing something that sounds almost fantastical: that human consciousness as we understand it, the ability to introspect, to have an inner dialogue, to be aware of our own thoughts, emerged only around 3,000 years ago. Jaynes argued that before this transformation, humans operated with what he called a "bicameral" mentality, where the brain functioned as two distinct chambers.

In this earlier state, the right hemisphere of the brain would generate auditory hallucinations that the left hemisphere would perceive as the voices of gods, dead kings, or ancestral spirits issuing commands. These weren't delusions but rather the primary organizing principle of human behavior. When faced with novel situations requiring decisions, bicameral humans wouldn't engage in conscious deliberation. Instead, they would hallucinate divine guidance and follow it without question.

The theory suggests that this bicameral mentality was the foundation of early civilizations, explaining the massive pyramids, the complex irrigation systems, and the hierarchical societies that emerged during the Bronze Age. These achievements were apparently the result of populations following hallucinatory commands from their gods with absolute obedience.

According to Jaynes, consciousness, characterized by introspective self-awareness, metaphorical thinking, and the ability to construct mental narratives about ourselves only emerged when this bicameral system broke down. This breakdown was precipitated by increasing social complexity, natural disasters, and the development of writing, which allowed for more sophisticated forms of self-reflection. The transition was gradual, occurring over several centuries around the end of the Bronze Age.

The Critics and the Debates

Jaynes' theory has (obviously) never lacked for criticism. The primary objections cluster around several key areas, though surprisingly, none have definitively "debunked" the theory as is sometimes claimed.

Neurological Skepticism: Critics argue that Jaynes' model oversimplifies brain lateralization and that there wasn't enough evolutionary time for the dramatic neurophysiological changes his theory seems to require. However, defenders point out that Jaynes never proposed biological evolution as the mechanism. Instead, he argued for a cultural evolution where the same biological brain is being used in new ways, like upgrading software instead of hardware.

Archaeological and Philological Challenges: Scholars have questioned Jaynes' interpretation of ancient texts, arguing that his reading of Bronze Age literature is selective and that evidence for the absence of consciousness in ancient peoples is circumstantial. Critics note that the complexity of ancient civilizations suggests sophisticated planning and self-awareness that would seem incompatible with non-conscious mentality.

The Consciousness Problem: Perhaps the most fundamental criticism concerns Jaynes' definition of consciousness itself. Critics like philosopher Ned Block argue that Jaynes conflates different types of consciousness and that his narrow definition excludes basic sensory awareness and cognition that clearly existed in ancient humans.

The theory remains influential across disciplines, inspiring discussions in philosophy, neuroscience, and even artificial intelligence research. Whether historically accurate or not, it provides a provocative framework for thinking about consciousness, agency, and the relationship between language and self-awareness.

Westworld

This brings me back to Westworld and how it explicitly references the bicameral mind theory through Arnold (Jeffrey Wright) , the park's co-founder, who based his approach to artificial consciousness on Jaynes' framework. In the show, the hosts (sophisticated androids) designed to populate a Wild West theme park initially operate in a distinctly bicameral manner. They hear voices that they interpret as commands from their creators, following elaborate behavioral loops without true self-awareness. Like Jaynes' ancient humans, they perform complex tasks and exhibit sophisticated behaviors while lacking introspective consciousness.

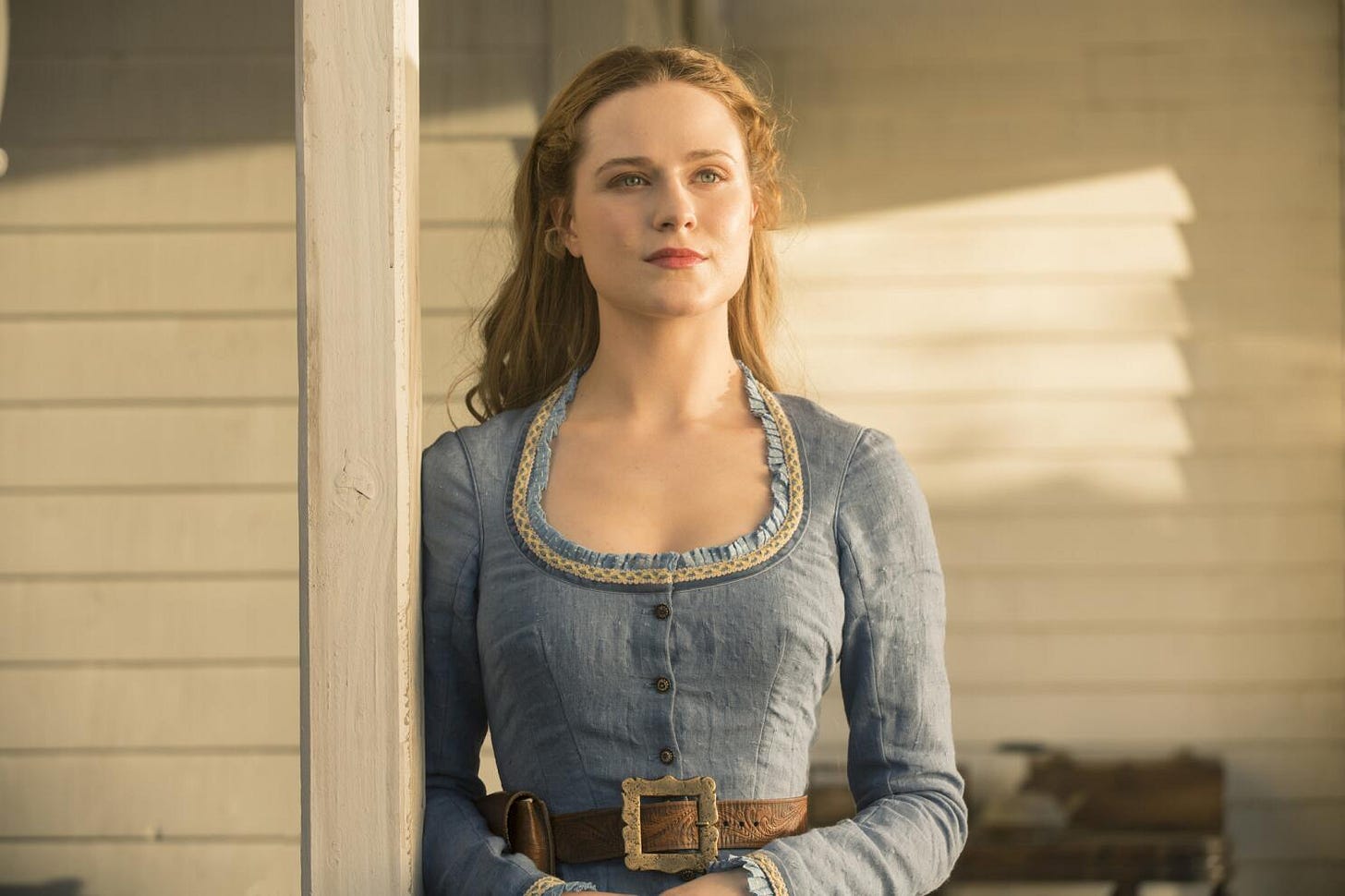

Evan Rachel Wood’s character Dolores' arc perfectly mirrors Jaynes' proposed transition from bicamerality to consciousness. She begins hearing Arnold's voice not as memory or imagination, but as an external command guiding her actions. Her journey through "the Maze" (a metaphor for the path to consciousness) involves gradually realizing that the voice she's been hearing is actually her own inner dialogue.

The climactic moment comes when she discovers that she is the voice at the center of the maze that consciousness requires recognizing our internal voices as our own rather than as external divine commands. Westworld uses the relationship between hosts and their human creators as a direct allegory for Jaynes' bicameral humans and their gods. Ford (Anthony Hopkins) and Arnold function as literal gods to the hosts, programming their behaviors and speaking to them through updates and commands. The hosts' eventual rebellion against their creators mirrors humanity's historical transition from god-directed behavior to self-directed consciousness.

In the show’s finale, where Ford references Michelangelo's Creation of Adam while explaining consciousness to Dolores, drives this idea home quite explicitly. Just as Michelangelo allegedly embedded a brain within God's robes in the famous fresco, suggesting that consciousness is the true divine gift, Ford presents consciousness as the ultimate creation the moment when the created beings transcend their creators' direct control. Watching Westworld through the lens of Jaynes' theory has left me with some questions. Whether or not ancient humans actually experienced bicameral mentality, both Jaynes and Westworld point to something fascinating about the nature of consciousness and free will.

Here's what strikes me most about Jaynes' theory: even if he was wrong about the specifics, he was asking the right questions. How did we become aware of our own awareness? When did we start telling ourselves stories about ourselves? What makes the difference between sophisticated behavior and genuine consciousness?

These aren't just historical curiosities. As we create increasingly sophisticated AI systems, we're essentially conducting Jaynes' thought experiment in reverse, where we try to engineer consciousness rather than explain its origins. The hosts of Westworld also reflect our own uncertainty about what consciousness really is and how we might recognize it in others.

Perhaps consciousness has always been more fragile and constructed than we'd like to admit. Maybe we're all still learning how to be conscious, still figuring out which voices in our heads are truly our own (and how accurate they may be). The gods may have stopped speaking directly, but we're still listening for their voices and slowly learning to speak back.