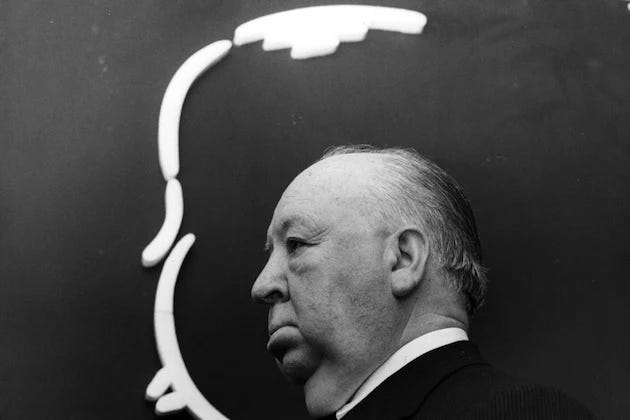

Although Alfred Hitchcock made over 50 films across six decades, there's something almost mathematical about the precision of his craft that makes discussing his "best" feel both impossible and inevitable. I find myself returning to the same seven films again and again, like a murder suspect revisiting the scene of the crime, each viewing revealing new layers of calculated manipulation.

Rear Window (1954)

Rear Window sits atop my personal pantheon because it's Hitchcock's most technically ambitious film. Stewart's L.B. Jefferies, confined to his wheelchair with a broken leg, becomes the perfect surrogate for every moviegoer who's ever sat in the dark, watching other people's lives unfold through a rectangular frame. I remember the first time I watched it, how Hitchcock gradually transformed my innocent curiosity into something more sinister, more shameful. There's that moment when Grace Kelly is searching through Thorwald's apartment and we can only watch from across the courtyard, powerless to intervene. Suddenly you realize Hitchcock has caught us red-handed. We're not innocent viewers anymore. We're voyeurs, and we're loving every second of it. Hitchcock understood that cinema is inherently voyeuristic, but rather than shy away from this uncomfortable truth, he builds an entire narrative architecture around it.

Rope (1948)

If Rear Window is Hitchcock's meditation on cinema itself, then Rope represents his most audacious formal experiment: an attempt to film murder as performance art. The film's famous "single take" construction (actually several long takes stitched together) creates an almost unbearable sense of real time unfolding, as if we're trapped at this dinner party with two killers who think they've committed the perfect crime. There's something super unsettling about how Hitchcock makes us privy to Brandon and Phillip's secret, forcing us to watch James Stewart's Rupert Cadell slowly piece together what we already know. Rope functions as both a thriller and a critique of intellectual arrogance. Brandon's Nietzschean philosophy (his belief that superior men are above conventional morality) becomes increasingly hollow as the evening progresses. Hitchcock exposes the fundamental emptiness of such thinking, showing how quickly intellectual superiority curdles into murderous narcissism when disconnected from basic human empathy.

Psycho (1960)

Psycho remains the film that most violently shattered audience expectations, and decades later, it still feels transgressive. The shower sequence is still one of cinema's greatest set pieces; it's a masterclass in how editing, sound design, and performance can create terror from the mundane act of bathing. But what continues to fascinate and unsettle me about Psycho is how Hitchcock makes us sympathize with Norman Bates, even after we discover what he's done to his mother and to God knows how many other unsuspecting guests. Hitchcock understood that the most frightening killers aren't the ones who seem obviously dangerous, but those who could be living next door, running the local motel, offering you tea and sandwiches before stabbing you to death.

Vertigo (1958)

Vertigo might be Hitchcock's most psychologically complex film, a meditation on obsession and identity. Jimmy Stewart's Scottie Ferguson represents masculinity at its most toxic — a man so consumed with reshaping a woman to match his ideal that he literally drives her to destruction. The film's famous dolly-zoom shots represent Scottie's acrophobia and they help us visualize the dizzying descent into romantic obsession, where love becomes indistinguishable from psychological manipulation. It’s Hitchcock's dark exploration of how men project their fantasies onto women, treating them as raw material to be sculpted rather than human beings to be known.

Strangers on a Train (1951)

Strangers on a Train takes the concept of the "perfect murder" and runs it through Hitchcock's moral universe, where seemingly casual encounters can unleash devastating consequences. The film's central premise: two strangers agreeing to swap murders, taps into a fundamental fear about how thin the line between civilization and chaos really is. Robert Walker's Bruno Anthony remains one of cinema's most chilling villains because his logic is so seductive, and his charm so genuine.

The Birds (1963)

The Birds stands apart in Hitchcock's filmography as his most apocalyptic vision, a film where the threat is nature itself turning against us. There's no explanation offered for why the birds attack, no resolution that restores the natural order. This absence of closure makes the film more disturbing than any of Hitchcock's more psychologically explicit thrillers. Hitchcock wanted us to feel the same helplessness as his characters, confronting a threat that couldn't be reasoned with, manipulated, or outsmarted.

Dial M for Murder (1954)

Dial M for Murder rounds out my personal seven as Hitchcock's most theatrical film, a chamber piece that proves his mastery wasn't dependent on elaborate set pieces or exotic locations. The film's single-location setting, mostly confined to a London flat transforms what could have been a simple stage adaptation into something cinematically vital through Hitchcock's understanding of space, blocking, and the psychology of performance.

Hitchcock's best films remind us that watching movies can be a morally complicated act, one that reveals as much about us as the characters on screen.

What's your favorite Hitchcock film? Let me know your thoughts in the comments and connect with me on Letterboxd